The Visibility Principle: How Internal Vulnerability Visibility Shapes Remediation Behavior

- Open (new tab):

/files/The_Visibility_Principle.pdf

If the PDF does not render, open it here:

/files/The_Visibility_Principle.pdf

Related Video

Introduction

The idea is straightforward: making internal vulnerability status visible across teams and owners can increase remediation participation and improve patch outcomes, both in rate and speed. Many security leaders operate under a management intuition: “what gets measured gets improved.” This post summarizes the psychological and behavioral mechanisms behind that idea, backed by research and practical observations. In particular, it focuses on how visibility interacts with perceived accountability, perceived surveillance, and behavioral deterrence, and why visibility can change day-to-day security behavior.

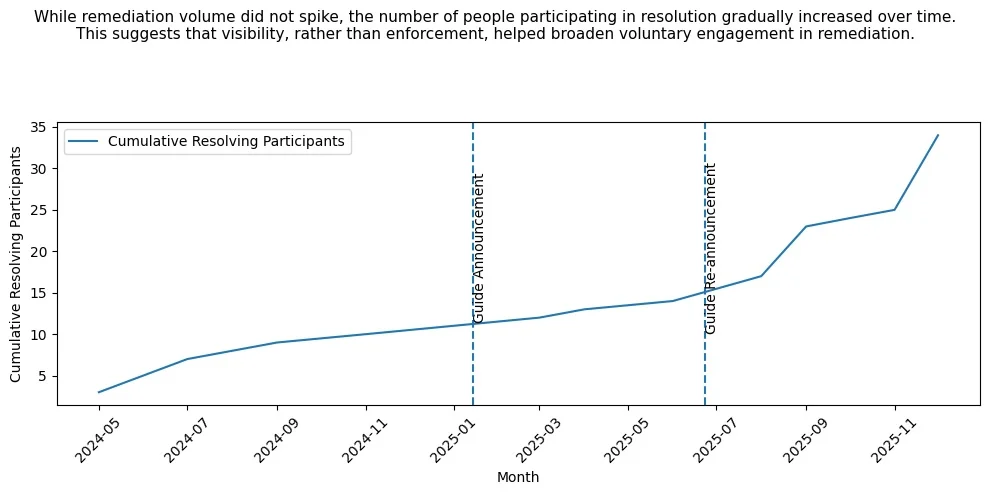

Figure 1. Even when remediation volume does not spike, the number of people participating in resolution can increase over time—suggesting that visibility (rather than enforcement) may broaden voluntary engagement in remediation.

Visibility and Perceived Accountability

Publishing internal vulnerability information tends to raise perceived accountability—the belief that one’s actions are identifiable and subject to evaluation. Research suggests that when people expect that their behavior can be attributed and assessed, accountability increases.1 Put simply, “everyone can see what I did (or didn’t do)” changes behavior.

Vance et al. (2015) also showed that UI elements that make monitoring salient (e.g., activity logging cues or access notifications) can increase perceived accountability and reduce intent to violate access policies.1 In practice, an internal vulnerability dashboard that makes ownership and status visible can create a similar effect: engineers and managers behave as if their remediation posture is being observed.

Security incidents are often cited as reminders of what happens when ownership is ambiguous. The 2017 Equifax breach is frequently discussed as a case where patching accountability and end-to-end ownership can break down in complex organizations.2 Conversely, when ownership and deadlines are clearly assigned and visible, a dashboard can increase the perceived cost of inaction and accelerate follow-through.2

Perceived Surveillance and Deterrence Effects

Perceived surveillance (“someone is watching”) is another mechanism. When people believe their actions are being observed, norm compliance often increases; some discussions reference this through frameworks like the Hawthorne effect. In security contexts, even the awareness of monitoring can be enough to shift behavior.1

The deterrence angle is supported by General Deterrence Theory: when people believe violations are likely to be detected and consequences are certain/severe/swift, compliance tends to increase.3 In practice, internal transparency can create an informal deterrence effect: fear of reputational damage, peer comparison, and social pressure—even without formal punishment. A meta-analysis suggests that informal deterrence mechanisms can be particularly effective in security compliance contexts.3

One caution: transparency can backfire if it becomes “name-and-shame” or punishment-driven. Some practitioners argue that metrics should not be used to stigmatize teams, because it can reduce reporting quality and create perverse incentives.4

In other words, the same visibility signal that increases compliance can also create unhealthy pressure if it is framed as blame. To ensure deterrence operates constructively, leadership needs to cultivate a responsibility culture (clear ownership + support) rather than a blame culture (public shaming + punishment-first).

Practical Patterns: Dashboards, Guides, and Reminders

Organizations often operationalize visibility through internal security dashboards and lightweight process artifacts. Industry writing frequently emphasizes visibility as a key principle: when status is visible, it becomes harder to ignore and easier to coordinate.5

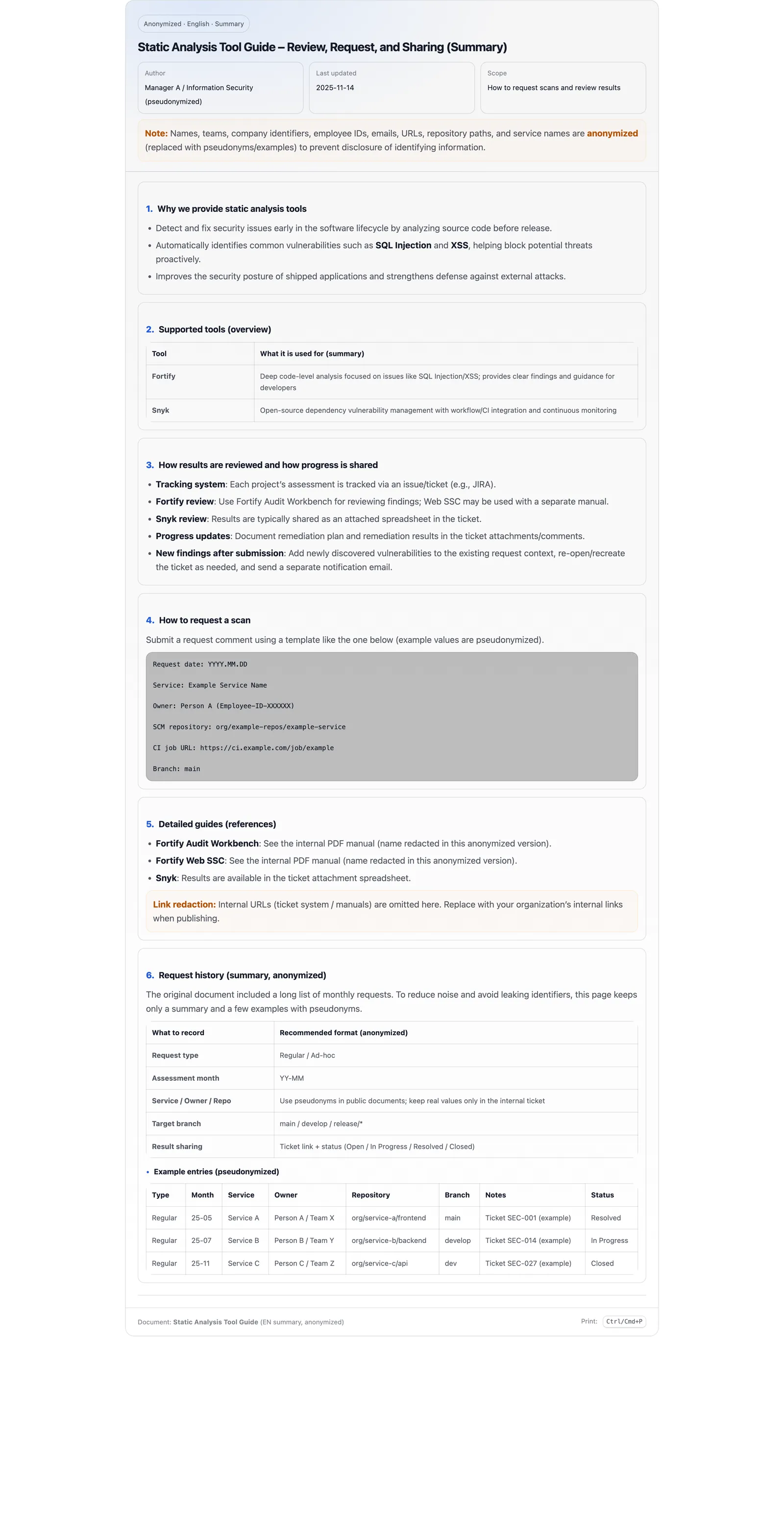

Figure 2. A one-page guide that standardizes how to request scans, review results, and share progress can reduce “process friction” and make status sharing routine.

Practical guidance also often recommends two simple moves: use a shared dashboard and assign a clear owner per item—both of which can reduce coordination cost.2

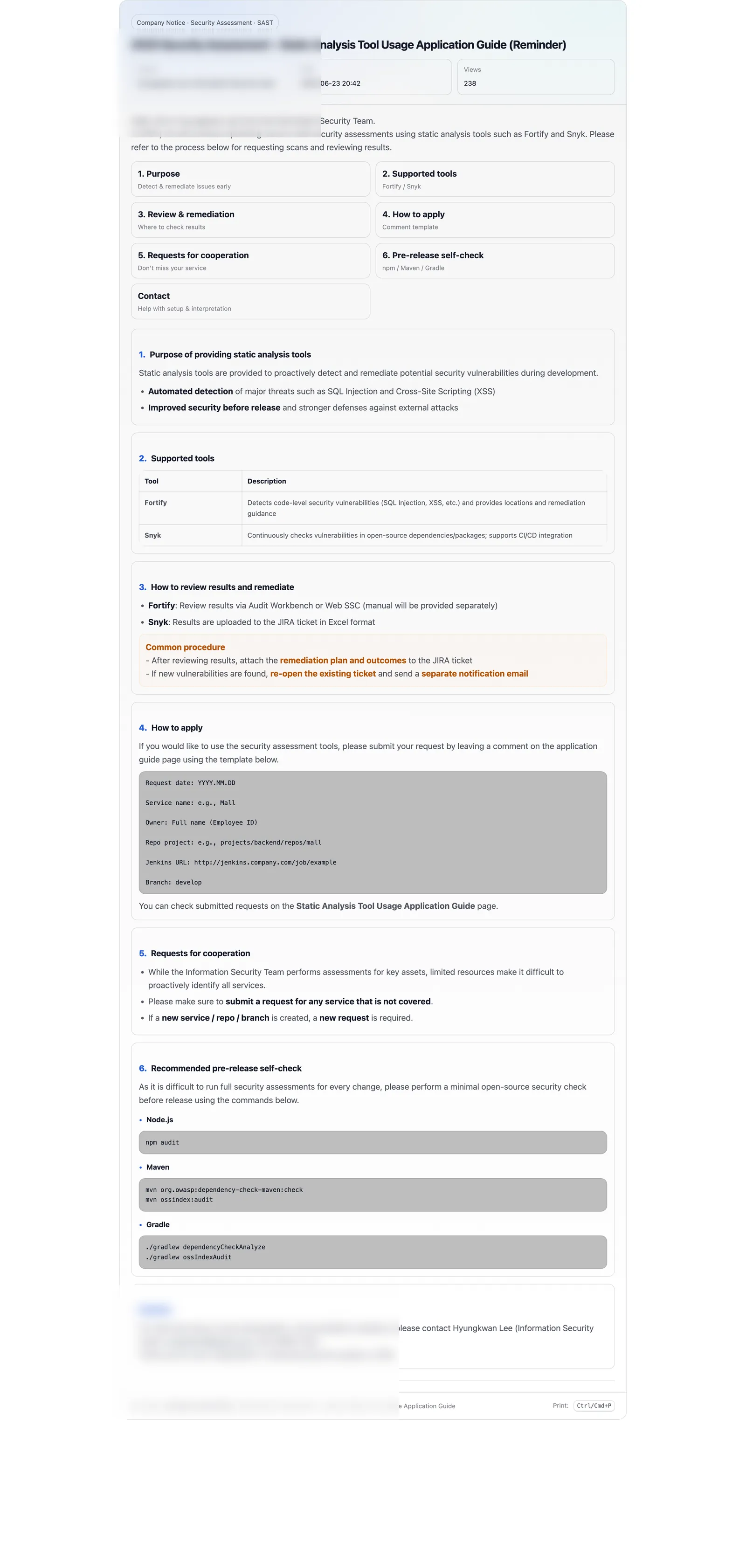

Figure 3. “Guide → reminder → broader participation” is a simple but effective pattern. In large organizations, repeated reminders and visibility signals can be more reliable than a single announcement. (Sensitive information was blurred for public posting.)

If you want to cite specific statistics (e.g., “X% of companies adopted DevSecOps due to patch speed”), it’s safest to link the primary report directly. Here, we keep the point high-level: collaboration improvement and patch-time reduction are repeatedly cited as motivations and outcomes in practitioner summaries.2

As another practical example, some practitioner write-ups describe a cross-functional cadence—e.g., a biweekly vulnerability review meeting—where security, engineering, operations, and compliance representatives jointly review open findings, agree on priorities, and make ownership and due dates visible to everyone involved.2 Because this is an experience-based narrative (not a controlled study), it’s best treated as an illustrative operational pattern rather than a statistically validated result.

The point is straightforward: when information flows smoothly and work is transparently tracked, delays and conflicts caused by role ambiguity tend to shrink.2

Empirical Takeaways and Practical Implications

Putting these mechanisms together, the improvement in remediation behavior from internal visibility is best explained as a combination of:

- Accountability: “My actions are identifiable and will be evaluated.”

- Surveillance awareness: “My status is visible to stakeholders (peers, security, leadership).”

- Informal deterrence: “Inaction has social costs (reputation, peer pressure), even without formal punishment.”

At the same time, transparency is not a silver bullet. If visibility is used only for “calling out” teams, it can create counterproductive behavior: hiding issues, optimizing metrics rather than outcomes, or avoiding reporting.4 The most durable pattern is to use visibility to drive coordination and support—clear ownership, clear deadlines, clear escalation paths, and shared context on what “good” looks like.

Conclusion

Transparency does not replace engineering. But it can change behavior: it increases perceived accountability, heightens the sense of being observed, and can create informal deterrence that nudges teams toward timely remediation. Done well, visibility becomes a coordination tool—done poorly, it becomes a blame tool.

The practical takeaway is simple: make remediation status visible, make ownership explicit, and make the process easy to follow. Visibility works best when paired with clear leadership support and a culture of shared responsibility.

One external example of “visibility pressure” is Google’s Project Zero disclosure policy: by setting a clear deadline for fixes and publishing details after the deadline, the policy is often credited with compressing patch timelines across vendors.6

References

“Increasing Accountability through the User Interface Design Artifacts: A New Approach to Addressing the Problem of Access-Policy Violations,” SSRN, accessed 2025-12-29, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2549000. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

“Patching the People Problem: Conflict Resolution in Vulnerability Management Programs | by Arturo Avila,” Medium, accessed 2025-12-29, https://medium.com/@arturoavila_da/patching-the-people-problem-conflict-resolution-in-vulnerability-management-programs-dc1a3e07401e. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

“https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167404820302042,” ScienceDirect, accessed 2025-12-29, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167404820302042. ↩︎ ↩︎

“Top 20 Worst Practices for Enterprise Vulnerability Management,” LinkedIn, accessed 2025-12-29, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/top-20-worst-practices-enterprise-vulnerability-carl-c-manion. ↩︎ ↩︎

Jason Chan, “From Gates to Guardians: Alternate Approaches to Product Security,” LASCON 2013 Liveblog – First Morning, The Agile Admin, October 24, 2013, https://theagileadmin.com/2013/10/24/lascon-2013-liveblog-first-morning/. ↩︎

“https://www.darkreading.com/application-security/google-s-project-zero-policy-change-mandates-90-day-disclosure,” Dark Reading, accessed 2025-12-29, https://www.darkreading.com/application-security/google-s-project-zero-policy-change-mandates-90-day-disclosure. ↩︎